From the autobiography of

Architect Jose Lorenzo de Ocampo

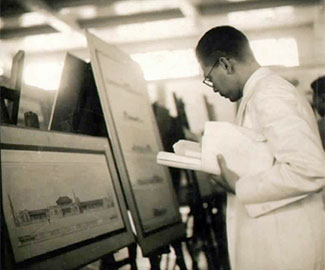

As a student at the University of Santo Tomas (UST), one of my professors, Architect Juan F. Nakpil, asked me to report to work for him at his firm. His staff consisted of five draftsmen (including myself) who were working on the plans for a church in Quiapo, as well as the drafting of plans for two residences. I was given the opportunity to participate in drafting plans for the Ateneo de Manila Auditorium, the Radio Theater, the Avenue Theater, and the State Theater, among several other buildings.

In 1933, I graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in architecture and my papa was so happy that he threw a party in my honor, to which naturally, I invited my beautiful “novia” Carmen Ravasco.

Carmen

I was a student at Ateneo High School in 1924, when Carmen and her family moved into the house across the way from us on Regidor street. From the window of our house directly in front of their second floor window, I saw her for the first time sitting at a sewing machine. I was awestruck and immediately knew that she was someone very special. In that moment, I decided that I would pledge my life to her and to be true to her.

Carmen's family were long-time residents of the district of Santa Cruz on Calle Sales, so they were known by my folks, especially my aunts, the sisters of my mother. Carmen was the oldest daughter of Jose and Olympia Ravasco, and the family spoke Spanish in their home. I recall that she was very young at the time, about fifteen, and, in addition to sewing she also enjoyed studying and playing the piano.

My father, Artist Jose Gabriel de Ocampo (who was also musically inclined and played the violin), by way of being a good neighbor and to renew acquaintances with the Ravascos, invited them to our home, and also, to hear Carmen play her favorite piece—Rondo Capriccioso. She graciously played, and when she finished and started to collect her sheet music, I noticed that the pages were tattered and torn from so much use. This gave me the perfect opportunity to offer to mend the pages, but not without first placing a short note (my first “love letter”) within the pages before returning it to her. As I handed the music back to Carmen I whispered quickly in her ear to be sure to look for my note inside. Not long after that however, the Ravascos moved away to another home on Antipolo street.

When I graduated Ateneo High School in 1925, Carmen attended my commencement ceremony accompanied by her aunt. And, even though her family had moved away, I continued to see my "novia" during the week. I visited her on Tuesdays, and then on Fridays, I usually met up with her auntie and together we would pick Carmen up in Quiapo after her piano lessons. Sometimes she would remain in Quiapo with her lola (grandmother) and aunties until she went home with her papa to Antipolo for the remainder of the week; on those days that she was in Quiapo, our visits would sometimes last until 10 p.m.

Carmen took on a part-time job in a small clothing shop when her aunties and lola moved to another home on the corner of Lepanto and Bilibid Viejo streets. In my spare time, I would try to meet up with her to walk her home. On Sundays, we attended mass at St. Sebastian church which was only a block away from her aunties home. After each weekend she would return home with her papa; and this routine continued until I completed university.

Marriage

On May 26, 1934, Carmen and I married. I was in the process of studying for my board exam while I worked on an embroidery pattern for Carmen’s wedding dress. “A Dios orando y con el mazo dando” (God helps those who help themselves) was my then motto back then.

Our union was officiated by the Jesuit Father Eduardo V. Aniceto at San Ignacio church in Intramuros. At the time, most Catholic weddings took place early in the morning (ours started at 7:30 a.m.) because eating prior to taking Communion was not permitted. The ceremony seemed to last a very long time and gradually I began to feel uneasy. As I knelt beside Carmen, a cold perspiration began to building up and slowly intensify. I felt my limbs begin to weaken as my vision grew darker and darker until the only thing visible before me were the flames of a candle set upon the altar. As I started to feel myself pass out, I began to call out Carmen’s name (or so I thought) and she clarified later on, that that wasn't the case; that in fact, I hadn't said anything. She did say that I looked very pale.

Our family and friends showered us with many gifts. Among them a Sala set consisting of a sofa, two chairs, and a center table; two rocking chairs; a China cabinet; a wardrobe with mirrored doors (I had designed the cabinet and Carmen’s grandmother had it made and gifted it to us); a bed with a matching nightstand (which I had also designed); a China set, tea set, and coffee set; glass wares; a statuette of the Sacred Heart, and a statue of Saint Joseph with the infant Jesus. All of these items burned to the ground in the fire that razed our home in Quiapo during World War II.

At around noontime on the day of our wedding there was an enormous downpour that prevented us from leaving the city to spend our honeymoon. Instead, our first night as husband and wife was spent in the entresuelo of our old family home on Rigedor street.

I considered 1935 to be one of my most lucky of years. I was blessed with three heavenly gifts – being married to the girl of my dreams, the birth of our first child whom we named Teresita (Tesy, our bundle of happiness), and passing the board exams, almost topping the list of successful candidates. The announcement of the results were published in the local newspaper in December, and at first, I couldn't believe it myself, garnering second place. It was a beautiful and wonderful Christmas present for me, and having Carmen and my little Tesy who brought with her the promise of a teaching position at UST.

In 1936, by a singular privilege, I became an assistant instructor at UST, and after paying the fee for the government permit and receiving my professional seal, I was now able to sign my name with the title Architect. My father was so proud that he had a bronze door plate with my name and title embossed "Jose L. de Ocampo – Architect" made and attached it to the wooden door of our home. It remained there until the home was burned to the ground in 1945.

War

Carmen and I rented out the first floor of the family home for a nominal fee. But, as Quezon boulevard was becoming more and more commercial Papa decided to convert the ground floor units of the house into stores. He rented one unit to a Chinese family for a Paciteria and the other unit to a Japanese family who transformed it into a Halo-Halo refreshments parlor. To give way to Papa's projects, Carmen and I would have to move and search for a new place to reside. By now, we had three more children – Nina was four years old, Isabel (whom we called Lita) was two years old, and our son Ramon was two months old; Tesy was six years old and attending Santo Tomas grade school.

My search for a new home was confined to the vicinity around my place of work. After looking at a few homes for rent, I found one behind the university on Dapitan street overlooking the campus. I showed it to my papa and he heartily approved. We barely stayed in our new home for a month however, when we heard on the radio that war had broken out. On December 7, 1941, the the Japanese army attacked a military installation in the Philippines. In an instant, we plunged from a period of joy into one of deep blackness, a vacuum of paralysis and not knowing what to do next. My first instinct was that we needed to reunite ourselves with Papa and Mama at the old house on Quezon boulevard, so we gathered what few belongings we could and returned from where we came.

In the turmoil that followed, people were moving here and there, and many were evacuating. Fear pervaded among the chaos and conflicting and terrifying news and rumors. The city of Manila was declared an open city. It was the last time I would see my brother Martiniano (Marty as we called him) who had joined the army. Before the war broke out, Marty was teaching at UST while also studying law, and on occasion, he'd come by our house to take the girls out for a ride in our Plymouth.

Japanese hordes were sweeping through the north in Lingayen, Bataan, and Corregidor—the last stronghold. By April 9, 1942, Bataan had surrendered. We had no news of Marty except for the whispers that his entire company had been brutally murdered as they tried to surrender; we were told, that they were left to die in the streets as they bled.

Every night I watched my papa seated near a window, unable to sleep as he waited for Marty to return home. He waited, and waited, and waited. We also searched, and inquired, and waited. As long lines of prisoners of war walked passed our home from the south in their death march to the north, our hopes and expectations would lift that we might find Marty alive and among them. That never came to be.

By this point my entire being was consumed with hopelessness. The university where I taught was closed and reduced to an internment camp for American prisoners; Filipino prisoners were sent to Capas, Tarlac. Our lives were grim and bleak, and the interior of our home matched that in darkness. In fact, the whole city was enveloped in darkness due to the blackouts ordered by the Japanese who were fearful of air raids and sneak attacks by the Americans. Papa had all of our windows covered with black drapes so that the light wouldn't show through to the outside. By now he was sick with a terrible and persistent cough and his health was deteriorating rapidly.

Radio Tokyo inundated our airways with broadcasts, and newspapers published by the Japanese regularly touted of successful exploits, including the details of American battleships that were sunk. In his exasperation, and bored with hearing of those accounts, Papa angrily crumpled the newspaper he was reading.

Papa

June 5, 1942, began the last remaining days of Papa's life. I woke up at 2 a.m. hearing him coughing and breathing heavily; he was overcome with weakness by now and Carmen and I were helpless in alleviating any of his suffering. He was bedridden from that moment on, and at one point muttered, “El principio del fin,” and I thought that that was the end. As the week progressed, his cough grew stronger and he complained of having headaches, so we called for Father Juan Anguela to administer last rites. In the days that followed, he was visited by the Reverend Father Jose Ma. Siguion who was the editor and publisher of the Catholic magazine Cultura Social where Papa had contributed numerous articles under the pen name JOB.

A few days later, Father Sigiuon visited again, and this time with two Benedictine priests – Father Paulino Garcia and Father Esteban. Then the next day, mass was held at our home by Father Juan Anguela and Papa received holy Communion. On Saturday, June 27th, the family gathered around Papa’s bed, including Mama; Carmen; our four children; my youngest brother Aurelio; my sisters Remedios, Maria, and Carmen; and Papa’s sister Tia Anastasia. I held a candle as I knelt at the foot of the bed, and then watched as he took his last breath.

Papa’s body was transferred to Quaipo church early the next morning where a requiem mass was officiated by the Reverend Father John F. Heley. There were so many priests in attendance that to the casual observer, one would have thought the deceased to be a priest. Papa's internment took place at 4 p.m. at La Loma cemetery and a Benedictine followed the cortege. Requiescat in pace.

Those who were more discerning of Papa’s character called him “el varon justo”—a just man. He was the loving father I knew, he was a good husband, the artist and painter, the maestro. He died and left us during the most crucial period of our lives – a time of danger and uncertainty, disruption and confusion, a time of invasion by a totally strange breed of people – rude and savage.

Everything was commandeered by the Japanese Imperial Army—all food stuffs including rice, corn, meat, vegetables, and fruit—we wouldn’t see a loaf of bread until the end of the war. Transportation was non-existent; our Plymouth was seized by the Japanese, and all radios had to be registered.

After Papa’s death, Mama became the center of gravity unto whose influence, we, her children, remained committed and united. As a small boy, I remember her posing for Papa, leaning on a window sill near the main stairs of our home. Every morning she would begin her day attending mass in Quiapo church, then she'd come home to change and head off to the market in Quinta. From there, she'd tackle a litany of chores and cook our meals. In the evening, the family would assemble in a cuartito for our daily Rosary and other devotionals like novenas. I have never seen Mama idle; she would either sit at the sewing machine – constructing or embroidering our clothing, vestidos or marineras; or, she’d sit at a table to the task of plying her fingers, fashioning silver beads and using delicate silversmith tools to hook them together into precious rosaries. On occasion, I would have the chance and the privilege to help Mama in her creations of these objects.

Surviving

The grief and the loss of my brother Marty, and then Papa, was further compounded by the imprisonment of two of Carmen’s brothers. They never returned. Also, my sister Remedios was apprehended by a Japanese soldier who accused her of making some kind of signal to the American prisoners of war who were being transported. We searched for her and when we found her, her hair was disheveled and her face and body were badly bruised and swollen.

In 1943, with no source of income, we discovered that Carmen would be having our fifth child. But through the merciful providence of God, and with the aid of a friend of my father-in-law Papa Pepito, I was able to secure a position at NADISCO (National Distributing Company) a newly formed business owned by a Mr. A. Aguinaldo. This occurred of course, with the approval of the occupying Japanese army.

Mr. Aguinaldo’s company distributed available food products such as Cassava, Panocha (small cakes of raw sugar), and canned fish. Rice, meat, and other more desirable commodities were hoarded and distributed by the Japanese. I came to appreciate the three years of commerce courses that I had taken in the past, and one particular skill that helped me to secure a job and thus save our family from complete destitution—my ability to use a typewriter. I walked to and from work every day in Binondo to type vouchers and receipts. It was also from NADISCO that I was able to bring home Cassavas and Panochas home to my family, the latter of which nourished our small son Ramon.

As the war continued and our despair grew, we clung to the hope and the promise of General Douglas MacArthur to return to the Philippines and liberate the country. One day while at work, we overheard the drone of aircraft and loud bursts of artillery above us. But, instead of scampering and hiding for protection, we ran straight to the rooftop of the office building to watch an aerial dogfight taking place. I saw a Japanese plane shot down and descend deep into the Manila bay in a huge plume of smoke.

Witnessing that was an incredible boost to our moral to know that MacArthur was making good on his “I shall return” promise. After that incident, there were more and more incursions and bombings of Japanese military installations throughout the islands by American war planes. The second dog I fight witnessed took place one morning on my way to attend mass at San Sebastian church. As I passed Calle Mendoza the intense blast of an air raid siren was sounded. Everyone walking along the streets ran for shelter where they could. I, and several other people, darted for a house with an open door as we saw bright with the early morning sky, two fighter planes engaged in battle. Once again, this event, rather than evoke fear, gave within us even more assurance that the Americans were coming to our rescue, and that peace would soon be with us.

Carmen began to have labor pains on the early morning of September 2, 1944. We were still under a strict curfew and had no means of transportation to take her to the clinic where our first four children were born. With no telephone to call for help, I began to walk to seek aid from the doctor on Bilibid Viejo street behind San Sebastian church. I had to pass by Raon street to cross over a small wooden bridge that spanned a creek, when I noticed a Japanese sentinel posted at the foot of the bridge on the other side. Having some familiarity of their customs, I bowed and tried to explain in broken language and with hand motions, my need for passing by. I believe my guardian angel carried me through with ease, as I was able to bring Doctora Matias with me to help Carmen deliver our fifth child, the only one of my children born in the original cradle of all the de Ocampos. We christened her Maria Consolacion Paz (Choly) in Quaipo church.

Hope Resurrected

As with any situation, inevitably there must be an end—so too a bitter one for the occupation of the Japanese Imperial Army. Since we really didn't have any means to know what was happening around us, we simply relied on our senses and observed the activities and movements of the Japanese soldiers; and we were beginning to see more of a restlessness and agitation about them. One morning, after a blackout evening, we saw a short wooden post erected across the width of Quezon boulevard; some said it had also been mined.

Several days later an explosion shook our house, and we learned that the Japanese blew up Quezon bridge out of a growing sense of desperation. We also noticed some Japanese soldiers and even officers passing behind and in between homes, and not through the streets. At around 10 a.m. on that same day, we saw a Japanese officer talking to Mama who was in the kitchen of our home. He then disappeared and squeezed himself in between the walls of the bathroom through to an adjoining building as though he was trying to escape. Once he was on the other side, in what was called the Life Building (a complex of offices and a movie theater), it was thought that he had planted a bomb. Fortunately, the bomb was discovered and diffused before it could detonate, thanks to our Lord God.

One very early morning we woke to the rumblings of heavy machinery and a loud voice coming from a speaker which was distinctly not Japanese. The noise was coming from the north near the building of the Far Eastern University, and presently being occupied by the Japanese army. As we looked out the windows we could see flares being directed towards that building. The voices grew louder and louder and it sounded like the Americans. We were right. General Douglas MacArthur was back! “I shall return” redeemed. At about the same time, a truckload of Filipino guerrillas invaded the UST grounds and liberated the American civilian internees and prisoners. Sadly, during this raid, my friend Manuel Colayco of Ateneo was killed.

Our joy of being liberated however was short-lived as the Japanese army—in their haste to evacuate—put the city to the torch. In a few short hours by noontime, we were forced to hastily grab what possessions we could carry and leave for safety. I remember Carmen reaching for the bottom drawer of our aparador to get what valuables she could, but left it to burn without taking a single item as the flames spread so fast. The fire was coming from the back of the house; our kitchen burned first, and soon the home was completely engulfed with flames. My mama and the rest of my family fled for a house across Quezon boulevard; I was the last to leave because I wanted to save my papa’s large painting among others that he had done. I couldn't believe that I was able to carry them as one was as large as 2 x 1.5 meters and encased in a heavy wooden frame—a painting of the signing of the Commonwealth constitution. Another one of his paintings was a life-size portrait of President Roosevelt, President Manuel L. Quezon, M. Roxas, the U.S. Secretary of State Curdel Hall, and other American officials.

I watched with great sorrow and an immense feeling of helplessness as so many things dear to us had been destroyed by the flames. The fire stopped there however, because of the width of Quezon boulevard, homes and other buildings standing across the way were spared. Through the graciousness of Mr. Ng, the owner of the New England hotel in front of our home, we were able to store Papa’s paintings and other personal effects in one of his rooms.

Carmen and our children—Tesy (now 10 years old), Nina (8), Lita (6), Ramon (4), and Choly (1) clinging to my mama—all walked to Calle Mendoza to take refuge in Mr. Ocampo’s Pagoda Tower. The place was crowded with people who were escaping the fire and we were all so terribly cramped. I recall the narrow stairway within and don’t quite know how we were able to pass the night in such a constricted and uncomfortable space. From our vantage point looking west we could not see a single home left standing. Everything within the historical Wall City – the famous Intramuros, all of the churches (except San Augusting church) were laid to waste and razed to the ground. The Americans had established themselves to the north, shelling without any letup, enemy forces and pushing them further south. In turn, the Japanese burned everything behind them as they retreated.

The very next morning, and to my surprise as we exited the Pagoda Tower, we were met by Carmen’s brother-in-law Patrocinio. He had come to look for us and had brought along with him a push cart for us to use. We loaded our few possessions into the cart, along with our two youngest—Ramon and Choly—and once again, were on the move in search of a home for our young family. We began our long trek far north to Calle Antipolo passing American soldiers as they continued their battery on enemy troops, and we ended our journey on Magdalena street in a school filled with refugees. There were a great many homeless taking temporary shelter here, and our family was assigned to a classroom with the family of Attorney Juan Cervania. A privacy screen of bed sheets had been strewn on ropes that were nailed to the walls. The parish church of San Jose de Trozo stood next door to our temporary home, and we attended Sunday masses here for several weeks. It was here that I came to know the parish Priest Father Jose B. Cruz, who soon after, asked me to remodel and design the facade of the church altar including the sanctuary. Our road to normalcy had thus begun, and so too finally, the onset of a new and promising chapter in our lives.

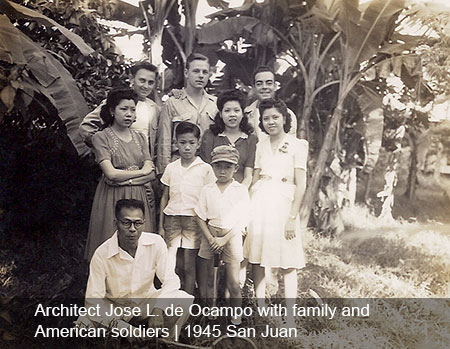

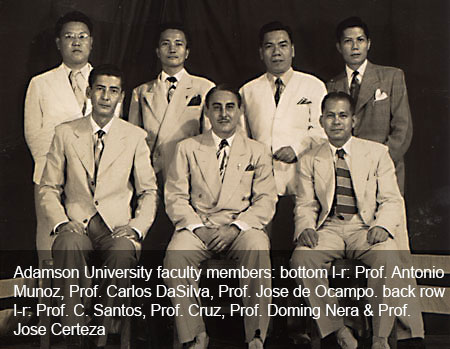

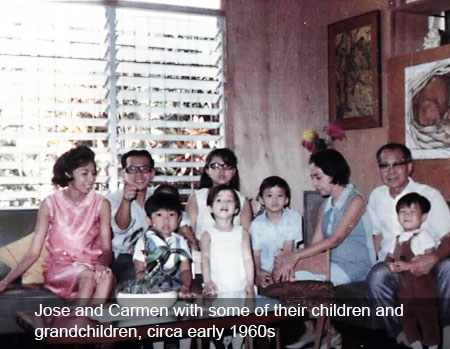

When World War II ended, Jose L. de Ocampo continued his career as an architect and also professor at the University of Santo Tomas and Adamson University (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jose_L._de_Ocampo).